In Part I, we discussed how labels (and entities operating as labels doing vanity pressings) ended up building a problem by releasing entirely too much product for customers to buy and absorb. The end result were additional costs that labels had hoped the distributors would prevent by taking on so much product for sale…paying for storage of product until it could be sold.

One of the major problems that labels and distributors encountered was the ability to use unsold product (returns) in place of repayment. So excepting a place like the original Tower records; most stores could stock albums that were newly released in the early window of their cycle and use the unsold stock to fund the next window of new releases. (If they sold out each title, it wouldn’t have been a problem.) It did not help that some record executives would often do outlandish things like release multiple 7″ singles by one artist on the same release day… or fear that their artists appeared to be lying on camera, so they would urgently press more copies to back a singer’s claim that her album shipped platinum when in fact it hadn’t until after that interview. It has been often said about Kiss that their solo albums shipped gold and returned platinum.* It doesn’t take long to determine that using product in place of money would create problems throughout the system.

In order to offload the albums whose sales potential were nil, some codes were needed to protect the labels from sending the undesired records out into the world at a discount only to have them used at full value as returned product against the bill for records that could still sell.

On 78 rpm records and early 45 rpm releases that came in plain storage bags, the answer came by putting a hole through the label portion of the disc that you could fit a #2 pencil through. Despite the blemish, the record would play fine, and it would be code to the distributors (and the label) that this product would not count if a store (or distributor) attempted to use it for return credit. As a result, many rare 45 rpm singles may have this blemish because so few were sold as a new release.

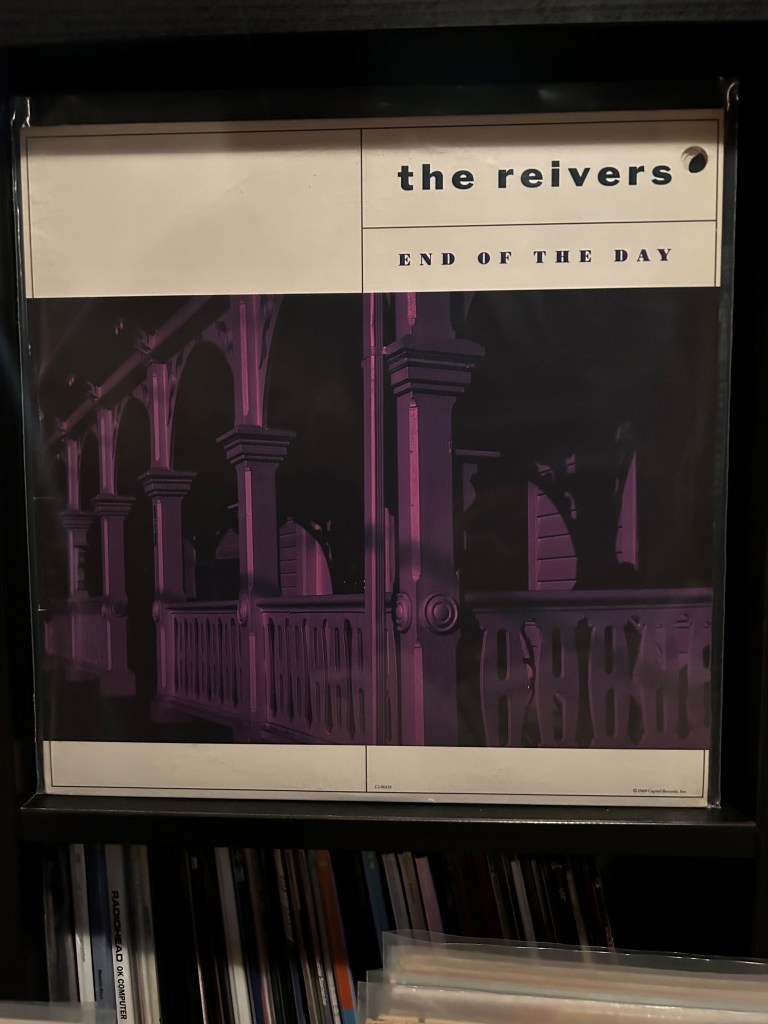

As picture sleeves became more common, as did cardboard album covers, they often would drill the hole in one of the four corners of the album jacket (away from the vinyl). Another way of ‘cutting out’ a record would be with what is called a sawcut. On the spine of such albums, there would be a notch cut into the jacket and its inserts (but again away from the vinyl).

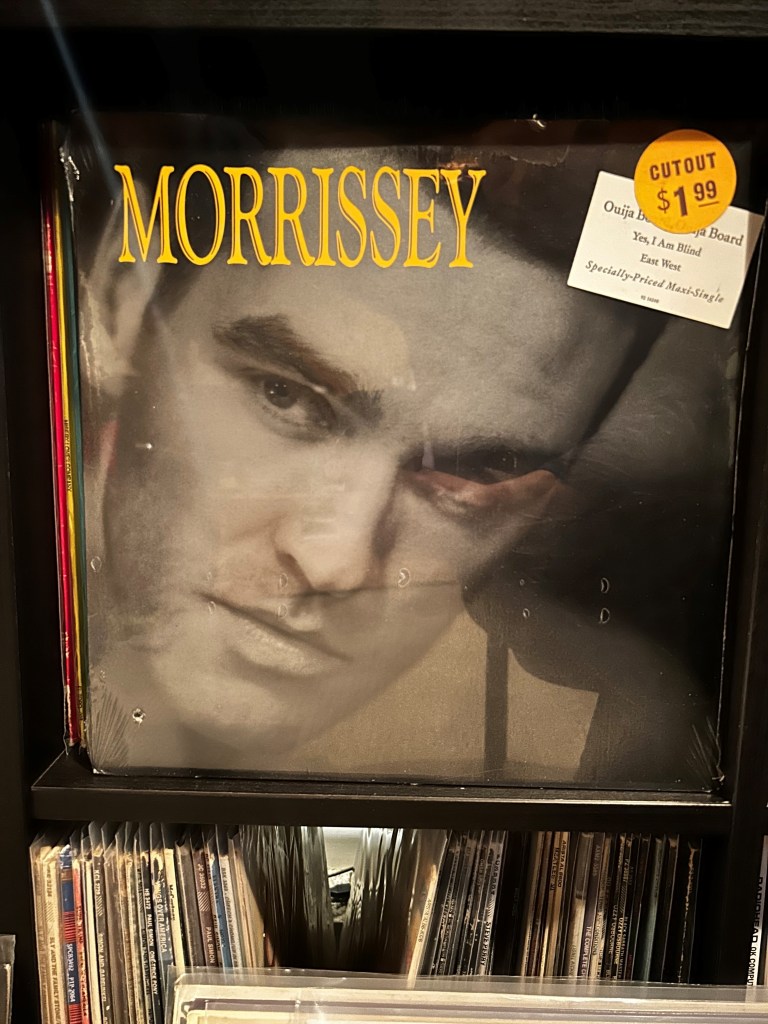

Eventually, there was a market for some of these cut-outs; which could be wholesaled relatively cheaply and then put into the market to sell at a price that was less than half the cost of an unblemished album. Despite the physical appearances of these products, the music played fine. Because of the markings (whether a hole, a notch, or other methods), the primary distributors and record companies didn’t have to worry about these being returned for cash… though it did create some controversy early on in the process. In addition, many of those vanity pressings would also be liquidated in such a way that they would appear alongside major label issues at department stores or supermarkets back in those times.

The controversy came as labels often did deletions on the fly. If a title was taken out of print, it would put out a notice to distributors in hopes that the news would get to retailers to send back the deleted titles before a certain date in order for it to be accepted as a return. The problem is that distributors and their retailers that missed the deadline now took the loss of value in the product. As a result, some cutouts actually bear no physical blemish, just the notation that it isn’t acceptable as a return or a credit. Some retailers also felt that the record company or its distributors were incredibly inconsistent in their explanations as to what could and couldn’t be returned at the time.

To offload the undesired products, labels not only sold the cutouts themselves, but would often enter into deals with distributors and non-traditional resellers of overstocked merchandise. It clearly created some upset among retailers to see cut-outs competing with new releases for customer dollars. In some cases, labels would include cut-outs with orders of new music (or of cut-outs) through distributors and directly to retailers. In addition, the non-traditional resellers who would put stock into places like gas stations and supermarkets; made for shorter release cycles from albums to hold full price to the discounted cut-out prices.

In addition to some of these headaches, labels often found themselves competing directly with liquidators who had purchased from their stocks of cut-outs at turn-and-burn prices before seeking out the same vendors the labels had intended to sell to for profit. In addition, record retailers seeing competition from non-traditional music sellers like supermarkets, gas stations, and department stores began creating cut-out sections of discounted music for fear of losing traffic and sales… even if it competed with more profitable newer releases in other sections of the store. Some labels were well aware that price consistency would be hard to maintain in the face of so much discounted merchandise; so for a short while, they chose to destroy remainders, deletions, and overstocked titles instead of discounting them. Though the sunk costs in the destruction of these products made for great news copy; eventually they reversed these decisions and began reselling again.

As mentioned earlier, cut-outs were initially holes punched into the label or into the corners of an album jacket. Some did sawcuts were were notch-cuts that appeared along the spine or toward any of the corners of an album jacket. When the market moved toward cassettes and compact discs; the hole-punches and sawcuts were done to the case and a portion of the inserts (even the longbox) for deleted titles to be resold in cut-out forms.

When UPC’s became common, these usually became the target of the cut-out markings. In time though promotional copies of albums, cassettes, and compact discs would also become part of the cut-out community. Especially in places that sold used product. So to close this out, let’s take a look at the various forms of cut-outs…

- Hole punches (or burns) directly through the plastic boxes of a cassette or compact disc does indicate that it was a deleted title and intended to be resold as a cut-out.

- Sawcuts that go through the box somewhere on the top or bottom of the plastic cases also generally indicate a deleted title and was intended to be resold as a cut-out.

- Sawcuts that appear on the spine were sometimes used as promotional copies (Capitol/EMI often did this to their in-store play copies in the early 90’s); but could also be resold as a cut-out (particularly if the shrink wrap is/was still present).

- Booklets that have a hole punched through them or a clipped corner were originally intended as promotional copies sent to record stores, radio stations, and media outlets.

- Hole punch through the UPC on the rear tray card of a cd (but not the case) was also initially intended as a promotional copy. (Sometimes there was a bb sized punch through the case at the center of the UPC… and during the late 80’s and early 90’s, WEA would also add a black and white WHEN YOU PLAY IT…SAY IT sticker to encourage its promotional use.)

- Writing on the cover or marker over lines of the UPC code are generally promotional copies as well. Some radio stations would also write their call letters on the cover of the insert booklet to ensure the cd would stay a part of its music library.

- Promo stamps near the UPC, on the cassette shells, or on the disc itself. MCA/Geffen/Telarc had a blue and white stenciled PROMOTIONAL stamp that would go directly on the compact disc… conversely, GRP would have a stamp on the disc marking “For Promotional Use Only…” as well as in place of a UPC code on the tray card of their albums throughout the 80’s and 90’s.

- Stickers on the cover of the insert booklets as well as on the face of the compact disc as well. (Most commonly seen on Impulse releases of the mid-to-late 90s. Variations on these stickers include the Capitol/EMI/Virgin white ‘patch’ sticker on the booklet and patch directly on the disc… as well as the gold-foil lettering on the cover of the insert booklet and sometimes on the disc itself used by WEA. These were meant to discourage stores from reselling the in-store play copies as used items after the release cycle.

Though originally considered part of the same discounted music family, are record club editions that came from the Columbia House Record Club or the BMG Direct service. Many Columbia House issues either have a CRC designation somewhere on the rear tray card; a “manufactured for Columbia House by…”, and often have a different catalog number than the original issue. Some CRC editions have UPC bar codes, but they are not the same as the in-store editions. In the case of the BMG Direct, usually there is a white patch in place of the UPC on the rear tray card (or later on an alternate UPC bar code number) that indicated it is a record club copy. As for cassettes and vinyl from these record clubs, the distinctions would require a separate article to explain.

From the 80’s through the 2000’s, it wasn’t uncommon to see lower values on cut-outs and record club editions at used shops. Many used shops would not buy back cut-outs or promo copies either. As downloading and streaming music became more common; fewer physical copies of albums are pressed and made available. Most promotional music only appeared in physical form on cd-r’s, but are mostly distributed through digital channels. The major record clubs shuttered nearly two decades ago. In addition, budget reissue labels like Flashback! and Geffen Goldline emerged to repackage and sell major label overstock at cut-out prices without having to blemish their products. As a result, cut-outs are generally only found on titles before 2005, and primarily among used music resellers. Lastly, newfound demand for deleted titles often fuel anniversary reissues and lavish remastered editions; particularly for less popular titles from very popular artists.

By looking at Discogs and other resale channels, the former prejudices against cut-outs, promos, and record club editions have faded with titles that have become rarer and harder to find. Some collectors consider these marks as patina versus blemishes and imperfections. It will be interesting to see if this becomes a continuing trend as the days of cut-outs go further into the past.

As I hit the exits, I do want to remind you that aside from a couple of years working at an independent record store and the consideration of making an investment into starting an independent label; that this comes from the mind and heart of a non-connected music fan who voraciously reads anything I can get my hands on from those inside the history. This account has the potential for minor inaccuracies based on my experiences rather than on insider accounts; but as a supreme music nerd; I appreciated the opportunity to share these ideas. In spirit of a true exchange of ideas, I look forward to hearing of your experiences in this area as well as making any needed corrections for when experience and reality didn’t match. Thank you again to the Cut-Out Kid for being the conduit of another musical discussion.

James Wayman is a music enthusiast, collector, musician, and educator from the far northwestern suburbs of Chicago. You can follow, comment, and/or react to his ‘album a day’ capsules on Twitter/X at @SMFOBA51.

Leave a comment