For a time, I was lucky to play with Adam and Rob in an indie-rock group called the Cut Out Kids (based on Adam’s rock/journalist alter ego, the Cut Out Kid). As a media obsessive, I knew immediately what the name meant. Though I was always surprised when talking about the project with others. Did people think we named ourselves after people who left things early or were we doubling down on a lack of athletic credibility never making the teams or getting left out?

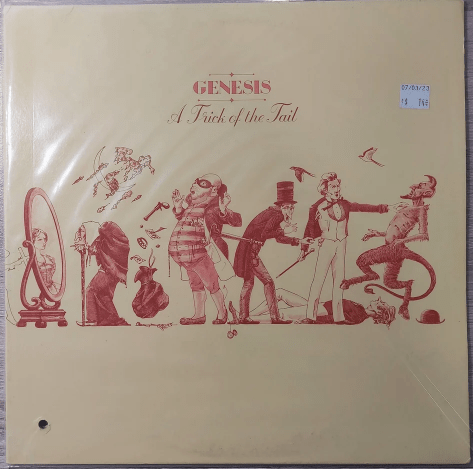

So long as there has been physical media, there have been issues with ways to produce, promote, sell, and close out an album’s initial run. In simple terms we won’t go into the grisly stories that resulted in artists getting into the studio or music getting made. For our purposes, we will just call it a record (but could be just about any physical format from 10″ – 78rpm discs forward.) It would be pressed for a specific number of copies (depending on if it was a regional or a national release). Once received from the pressing plants, the label and its agents would go to work on trying to sell through the stock without at least breaking even on the endeavor.

In the worst case scenario, an artist or band may do a vanity pressing that basically was a money dump. They may have overestimated the potential number of customers or how difficult it would be to enter the usual pipelines that brought songs to radio, records to press, and stock to places where people could buy it without having to know the artist personally or see them perform in concert. However this also happened to actual record labels too.

The label and its agents would receive the boxes of product and divide the stock into several categories. Many of the records would go to distributors (national or local) who were contracted to get them to retail locations. Many of these agreements were product-first in that the distributor would take a certain number into inventory on credit. When the note came due, the distributor could either pay it back with unsold product or money. Some distributors also were able to get extensions on the initial credit, where instead of a monthly statement, it might go 90 days, 6 months, or even a year. The distributors didn’t just deal with stereo or record stores; but also had agreements with other companies to put stock in department stores, drug stores, and even gas stations. The distributors had similar agreements with their retailers where the balances could be repaid with unsold merchandise as well as with money. Retailers would also get credit for defective stock as well.

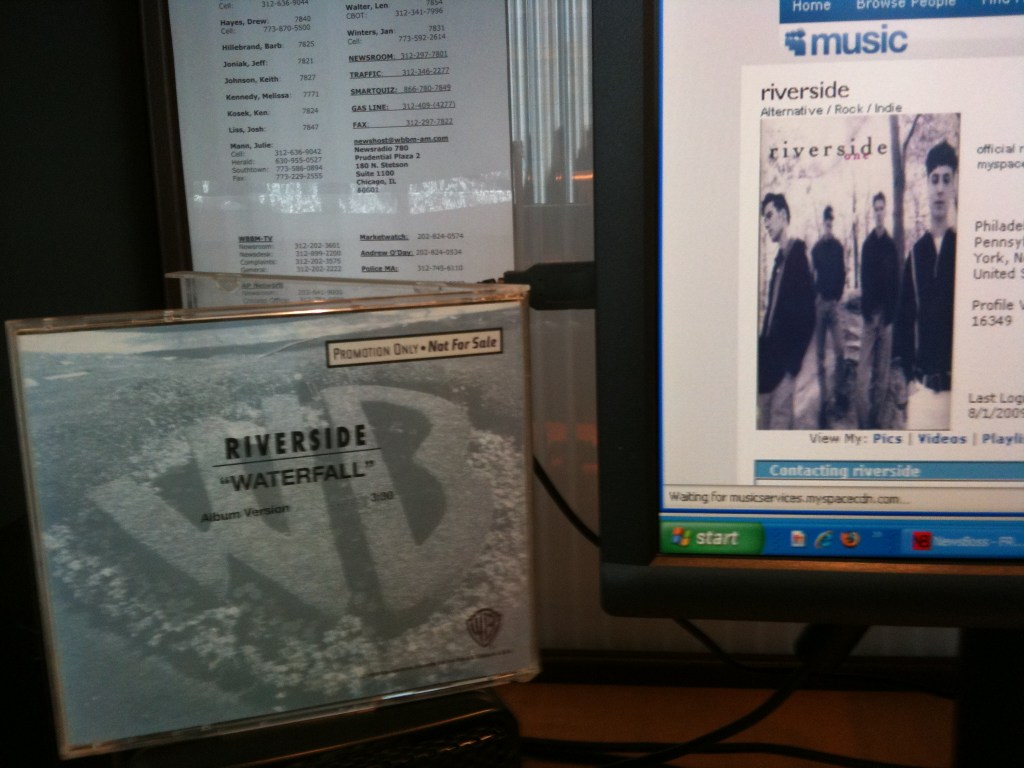

A portion of the records would be sent to promotional outlets, such as radio stations, newspapers, and (later) music magazines. There are a number of stories a Google search away from the way radio worked pre- and post-payola (where radio disc jockeys would receive money or other compensations for adding an artist’s single to their playlists). In many cases payola defined the how the business would turn as stations started using program directors to determine what went on the airwaves… (making promoters only have to bribe one person at the station versus all of the on-air talent…) After the 90’s when the number of media outlets an owner could have in a territory and nationwide increased, the number of people who needed to be influenced to get a song on-air was further reduced (though that person ensured play nationwide instead of just that territory). Though, those artists who didn’t have the budget for ‘radio promotion’ where a person would come in person to pitch the song to DJ’s or program directors; still sent records to the station in hopes that maybe it would break through. Some of the records would be used to make a press kit to send to newspapers and music magazines for review or whatever other coverage could be mustered. In addition, more records may be sent to be given as prizes in the contests and promotions held by these various outlets. These copies would have some sort of marking (or acquire a marking by the outlet) to note that these records weren’t for sale.

In some cases, artist managers and promoters would also include some records into press kits that would be sent to talent buyers at various music venues in hopes of being able to set up a promotional tour of concerts and appearances. These records would also be marked as not for sale. Later on, the managers would also buy records from the label to sell at the artist’s merch tables along with t-shirts, posters, keychains, and tour books. Though this was really uncommon until Napster and digital music led many territories to lose a chunk of their local retail outlets where a customer could purchase the album in store and in person.

The label would often have a stockpile of records remaining just in case of an unexpected event that brought attention to the artist or that odd event where an unexpected single might emerge that brings new interest to that record. For the most part, a record’s release cycle which could be anywhere from 90 days to 2 years after its release date. When the record had finally cooled off, it would be time to see how much stock was left at the label as well as how many returns came back from the distributor as repayment.

For an artist with a high national profile like Frank Sinatra, the Beatles, Michael Jackson, or Pearl Jam; the labels new there would be an opportunity to sell the older albums when the next album projects would be released; so to have some excess stock of these artists wasn’t particularly a concern. However, you only need to look at a time frame like the late ’60’s where it has been suggested that one hit artist actually subsidized the development of 8-10 more artists. One win bought more lottery tickets. The numbers game suggested that after the first hit; that there could be a hit among the next wave; a few others that would at least recoup expenses; and because of this, the artists that flopped didn’t matter as they were funded on house money.

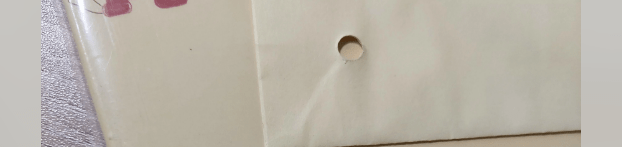

“These are not the ‘cut outs’ we speak of.”

It wouldn’t be long when this strategy started to backfire. New hits were being paid back from distributors with returned product from the flops of the last wave. All of a sudden, labels had to determine how to house a lot more records than they had planned. Let’s not forget about the many people who also did vanity pressings of their music only to wind up filling a basement or a garage with unsold product. Though what to do with excess inventory would always be a concern…

James Wayman is a music enthusiast, collector, musician, and educator from the far northwestern suburbs of Chicago. You can follow, comment, and/or react to his ‘album a day’ capsules on Twitter/X at @SMFOBA51.

Leave a comment